Conceptualizing the anti-ought-to self: Background and new directions

Amy S. Thompson – West Virginia University

INTRODUCTION

In some cultures, from an early age, children are encouraged to complete certain, perhaps challenging, tasks by using a form of reverse psychology (i.e. telling them that they are not able to do the task at hand). Take, for example, the scene I witnessed at the University of Nottingham, after the conclusion of the International Conference on Motivational Dynamics and Second Language Acquisition in August of 2014. I was in the early stages of my research into what was coined the anti-ought-to self, a self that thrives on excelling at challenging and unexpected endeavors. As I was in the lobby of the De Vere Orchard Hotel, having presented a paper entitled “The Anti-Ought-to Self and the Ought-to Self: The resulting synergy of two potentially conflicting attractor states,” my mind spinning with the ideas that abounded from the conference, my attention was drawn to a family with a small boy. The boy was fidgeting and refusing to complete his puzzle, which was intended to entertain him during Sunday brunch. One of the women in the group said, “Oh, Johnny can’t do this puzzle, can he? It must be too difficult for him.” The woman directed the speech at the other adults, but it was clear that she was really talking to Johnny. Johnny, almost immediately, went over to the puzzle and started working on it. “See? I CAN do it!” he said. Johnny, intent on proving the adults wrong, diligently worked on the puzzle while the adults enjoyed their brunch. A much-used tactic to trick children to do something that they are wary to do, this simple example epitomizes the core idea of the anti-ought-to self.

What is the anti-ought-to self?

The anti-ought-to self has been theorized to be part of Dörnyei's (2009) L2 Motivational Self System (L2MSS). The L2MSS can be thought of as a two-part theory to describe language learning motivation: the selves and the language learning experience. In terms of the self aspect, the original conceptualization of the L2MSS included ideal and ought-to selves, which were inspired by the work of Higgins’ (1987) concept of self-discrepancy theory; indeed Higgins coined the terms ideal self and ought self (which Dörnyei changed to ought-to self) in this seminal work. Also influential in the development of the L2MSS was Markus and Nurius' (1986) concept of possible selves.

The ideal self describes the desires of language learners in terms of who they aim to become in terms of language ability (internal desires). Visualization is a key facet of the ideal self; thus, terms such as “imagine” or “envision” are oftentimes part of data collection tools. The ought-to self is a self born of obligation (perceived or actual). It is the self that language learners feel pressured to become by some combination of those in their professional or personal circles. Of the ideal and ought-to selves, the ideal self has typically been found to have a stronger connection to successful language learning, whereas the ought-to self has not typically demonstrated similarly strong results (Csizér & Lukács, 2010; Lamb, 2012; Thompson & Erdil-Moody, 2016).

Some researchers have found the ideal and ought-to selves lacking in terms of providing the full range of possibilities for self development. For example, in examining narrative data for their article, Thompson and Vásquez (2015) found the current L2MSS lacking in terms of concepts of selves, as they found two of their participants, Alex and Joe, to be primarily motivated by a self formed by proving to others that they could do what was unexpected, namely learning Chinese (Alex) and German (Joe). Hence the anti-ought-to self was born. Inspired by Reactance Theory (Brehm, 1966), the essential characteristic of the anti-ought-to self is bucking the system, so to speak, or resisting/rebelling against certain societal expectations. This reactance can manifest itself in different ways, depending on the individual. An example of psychological reactance outside of the language learning sphere is a child getting a belly button ring or tattoo to rebel against his or her parents. Teenagers, as we know, frequently want to engage in activities that they are explicitly forbidden to do by their parents or guardians. Reactance Theory has not been used much in terms of theory-making in applied linguistics research; however, psychologists who work in language learning have previously cited it as a potential explanatory factor for different types of motivation (Goldberg & Noels, 2006; MacIntyre, 2002).

Thompson (2017a) illustrates a conceptualization of the selves in terms of individual dominant versus context dominant. For the ought-to self, the “dynamic interaction between learners and context can be conceptualized as learners being the “submissive” component and context as the “dominant” component (i.e. the external pressures prevail)” (p. 39). The inverse is true for the ideal self “which can be conceptualized as learners being the strong element, in charge of their own destiny” (p. 39) The anti-ought-to self is an externally-influenced self, like the ought-to self; however, like the ideal self, the learner is the dominant force, actively pushing back against societal expectations as an important part of their language learning motivation. Further illuminating the anti-ought-to self, Thompson (2017a) writes the following:

The anti-ought-to self can emerge when engaging with a commonly-studied language (such as English in the Chinese context), if one were to choose a language major over something potentially more lucrative (such a degree in engineering or medicine), as well as with a language that is less commonly studied (such a language other than Spanish in the U.S. context). The anti-ought-to self can develop in both foreign and second language contexts, and includes “ought-to” in the nomenclature because of the strong influence of events and pressures outside of the learner as the primary motivating components of this self guide. The anti-ought-to self could also have a relationship with the ideal self, being that the visual concept that learners associate with a successful language learning process is, in fact, to do what people do not expect them to do. Incorporating the anti-ought-to self into the L2MSS would allow for the type of future self that defines the learner as the prevailing force in the language learning process (p. 39).

There is certainly room for further explanation of this concept, as indicated by Dörnyei and Al‐Hoorie (2017); they postulate psychological reactance, and the resulting anti-ought-to self is a “special, and highly intriguing, aspect of the ought-to L2 self dimension of LOTE learning” (p. 461). The following sections will explore potential avenues for measurement of the anti-ought-to self, the role of context in the development of the anti-ought-to self, and other constructs in applied linguistics that are potentially related to the anti-ought-to self.

Measuring the anti-ought-to self and the role of context

Do all language learners possess an anti-ought-to self? As psychological reactance is primarily envisioned as a Western ideology (Laurin et al., 2013), I was surprised to find the anti-ought-to self construct in China in one of the first quantitative analyses of the anti-ought-to self (Liu & Thompson, 2018; Thompson & Liu, 2018). These items were developed using narratives from Thompson and Vásquez (2015), focus groups, and other discussions, and were used for the first time in the Chinese context. The items were designed as 6-point Likert-scale items to remove the neutral option for participants (Dörnyei & Taguchi, 2010). Table 1 below provides the items developed for the anti-ought-to self that have been subsequently incorporated into questionnaires measuring the L2MSS along with the ideal and ought-to selves.

Table 1: Anti-ought-to self items

|

Anti-ought-to self |

|

1. I am studying this language because it is a challenge. |

|

2. I want to prove others wrong by becoming good at the language I am studying. |

|

3. I chose to learn this language despite others encouraging me to study something different (another language or a different subject entirely). |

|

4. I enjoy a challenge with regards to learning this language. |

|

5. I would like to reach a high proficiency in this language, despite others telling me that it will be difficult or impossible. |

|

6. I am studying this language because it is something different or unique. |

|

7. I am studying this language even though most of my friends and family members don’t value foreign language learning. |

|

8. I want to speak this language because it is not something that most people can do. |

|

9. I want to study this language, despite other(s) telling me to give up or to do something else with my time. |

|

10. I am studying this language because I want to stand out amongst my peers and/or colleagues. |

|

11. In my language classes, I prefer material that is difficult, even though it will require more effort on my part, as opposed to easier material. |

The language in question can be altered depending on the context. For example, item 1, “I am studying this language because it is a challenge” could be changed to indicate a specific language if only one target language was being investigated. For example, the statement could be, “I am studying Chinese because it is a challenge.” The same could be done with all of the items. Exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) were used in these initial studies, resulting in three-pronged factor structures with the three selves (ideal, ought-to, and anti-ought-to) for English (Liu & Thompson, 2018). The clear division of selves indicates that the anti-ought-to self is not an overlapping latent variable with the ideal and ought-to selves. The emergence of the anti-ought-to self with the Chinese participants is particularly noteworthy, given the collective nature of the context. It should also be noted that in this context, the selves emerged in different ways, depending on the language in question. In Thompson and Liu (2018), not only English, but also French and Japanese, were examined. Looking more closely at the English majors, who were also required to take other languages, it was found that there was a clear-cut separation of the anti-ought-to self when looking at English and Japanese, but not when looking at French. Although English is a commonly studied language, these English majors might have felt pressure to excel at English, or they might have been pressured to major in a field other than English. There is also evidence that although English is valued in the Chinese context, the Chinese language is valued more (Liu & Zhao, 2011); thus, students would have to overcome potential suspicions regarding their desire to excel in English. In the Chinese context, Japanese is considered to be a necessary, but not necessarily loved, language (Deping, 2003). French is considered to be a popular, although not politically necessary, language since the formation of the People’s Republic of China (Xie, 2000). The distinctions between the ideal, ought-to, and anti-ought-to French selves for these Chinese students were potentially blurred because of the relative neutrality of French in China.

In another study, also in the Chinese context, Chen et al. (2021) analyzed data from Chinese students studying German and French. Generally speaking, these participants did not see the value of learning these languages for their future careers; instead, they were learning LOTEs as “an investment of effort to develop their personal comprehensive literacy, a cultivation of interest, a way to broaden horizons and a means to seek emotional fulfilment and satisfaction” (p. 91). Similarly to the Thompson and Liu (2018) study, English was considered to be by far the most useful language for careers, which was not the case for the European languages in question.

The anti-ought-to self is an important construct to examine when exploring the motivational profiles of students who are studying a Less Commonly Taught Language (LCTL). Using a questionnaire administered three times, interviews, and course artifacts, Pastushenkov and McIntyre (2020) longitudinally examined the motivational profiles of two L1 English-speaking learners of Russian. For the questionnaire, the authors used six of the anti-ought-to self items in Table 1 above: items 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 9. With their L1 English-speaking American participants who took part in the Major Critical Languages Program (MCLP), Pastushenkov and McIntyre (2020) found the anti-ought-to self to be an important characteristic in their motivational profiles. This was especially the case with Katia, who remained engaged with the Russian language, even after the completion of the program. The researchers tracked the participants’ selves before the start of the program, immediately after the program, and then again several years after the program. Katia maintained high ideal and anti-ought-to selves, potentially because of her continuous immersion with the language and culture, and the authors recommended examining the anti-ought-to self profiles of similar learners in future studies.

Other studies have used these specific quantitative items to measure the anti-ought-to self. For example, Thompson (2017b), found that Spanish learners had a significantly lower anti-ought-to self than those learners of any other language, perhaps because of the expectations of Spanish language study in the U.S. context. Huensch and Thompson (2017) found a relationship between the anti-ought-to self and the desire to improve pronunciation in the target language.

There are also more open-ended ways to get data on the anti-ought-to self. For example, in a survey sent to undergraduate students enrolled in language classes at West Virginia University, the following open-ended question was included: “Has anyone (friends, family, advisors, etc.) tried to discourage you from language study, either in general or for a specific language? If so, what made you continue? If not applicable, please write "N/A". Surprisingly, only about eight percent of respondents out of the approximately 1400 students who responded to the questionnaire indicated that they had faced resistance to language study. Those who did face resistance did so for reasons such as people’s perceptions of the difficulty of the specific language, advisors wanting students to stop studying the language to graduate faster, friends’/family members’ attitudes, questions about the language choice itself, and the perception that English is the only appropriate language to speak in the United States. The comments ranged from simple statements such as, “My dad says French is useless” to the more colorful descriptions, such as, “My friend Travis says I’m wasting my time and money, but he’s been working at a local grocery store in our small town and living with his mom since high school, so what does he know?” Thompson (2022) further illustrates anti-ought-to self results in the West Virginia context, while also comparting the results to similarly collected data in the Florida context.

Using the anti-ought-to self to interpret results

Similar to the Thompson and Vásquez (2015) study, data illustrating characteristics of the anti-ought-to self can emerge from the data, even when the focus isn’t explicitly or intentionally on this construct. Amorati (2021), in a study examining the motivations of German learners in the Anglophone context of Australia, received some interesting data from open-ended questions regarding German language study, such as, “What is your main motivation for studying German?” One of the participants indicated, “I feel like not learning a second language and expecting others to know English is a bit lazy.” Another stated, “It is ignorant of anyone in the global arena to only speak one language” (p. 187). Amorati linked such statements to the anti-ought-to self and related constructs:

These learners’ motivational dispositions can also be explained by drawing upon the notions of the “anti-ought-to self” (Thompson and Vázquez 2015) and “rebellious self” (Lanvers, 2017), which both describe the motivation to study a language in order to go against external expectations. These motivational dimensions are particularly relevant for learners of languages other than English in Anglophone countries, where monolingualism represents the social norm and where language learners may wish to create an “anti-stereotype” (Thompson and Vázquez 2015: 166) by rejecting the image of Anglophone speakers as poor at languages (Busse & Williams, 2010; Oakes, 2013, p. 188).

Indeed, this study illuminates the relative likelihood for an anti-ought-to self to emerge in an Anglophone setting because of the seemingly non-reliance on languages other than English (LOTEs), an attitude summed up in the comment from a participant in Thompson’s (2017b, 2022) data: “I have felt strong resistance from family and co-workers to NOT study anything but English. Some of the people closest to me have made fun of my language learning both directly and indirectly. Directly I have been told that ‘this is America and we only need to speak English.’ Also, indirectly I have heard people make jokes about language learning in English but with a foreign accent with the intention of belittling speakers of other languages” (Thompson, 2022, p. 106). Regarding this topic, Lanvers et al. (2021) delineate the challenges of learning a language other than English in an Anglophone context, and illustrate innovations by educators on how to overcome this obstacle.

Similarly, Salaberri-Ramiro and Sánchez-Pérez (2018) incorporate the concept of the anti-ought-to self in their discussion of the views of students in a Spanish state university with regards to their motivation to participate in their higher education bilingual program. In particular, students questioned why English was the only language other than Spanish (the L1) incorporated into their degree programs. One student stated, “We know that English is the language of global business, but why don’t we learn also through other languages like French or Arabic? I would like to work in the north of Africa when I get the degree” (p. 70). The authors conclude that “In the same line, they manifest critical views on the dominance of an EMI [English as the medium of instruction] approach which rejects the use of the L1 in class or inhibits the use of other foreign languages which can be considered a motivation based on the anti-ought-to self” (p. 71).

Looking at the role of selves and motivation from a different perspective, Crossley (2018) argues for the potential ebbs and flows of motivation, including the anti-ought-to self, if a society were to utilize machine translation in place of interpersonal interactions:

In such a case, the advent of simultaneous machine translation could decrease the motivation to learn a lingua franca such as English. Specifically, attitudes toward ought-to-self and anti-ought-to-self may change radically if society adopts simultaneous machine translation software as a means of effective interpersonal communication between speakers of different languages. Society may come to see learning a new language in an FL environment as an antiquated endeavor akin to using a horse for transportation or relying solely on a postal service for communication with friends and family. This technology-facilitated shift in the cross-linguistic communication habits of people worldwide may in turn affect the ideal self in that the perceived value of learning a FL may gradually decline for many populations (p. 547).

These studies indicate how the anti-ought-to self construct can be used as an explanatory variable, even when it is not the primary construct of investigation. For syntheses of motivation studies that include the anti-ought-to self, Mendoza & Phung (2019) include the concept of the anti-ought-to self in their critical research synthesis of motivation to learn LOTEs and Al-Hoorie (2018) discusses the anti-ought-to self in his meta-analyses of the L2MSS.

The dark side of resistance

The core concept of the anti-ought-to self hinges on using a sense of defiance to ultimately succeed in language learning. However, there is another, darker side of resistance, that results in demotivation. In the current volume, three articles by El Abbadi, Gacemi, and Popica and Gagné are illustrations of this point.

El Abbadi (2021, this volume) analyzes Moroccan high school students’ resistance to writing in French. In the study, the students seemingly resisted writing because they found the tasks too difficult. When assigned pair or group work, they found it difficult to work with their classmates and weren’t focused on the task, as one participant, Hassania, stated: “Je préfère faire autre chose, pendant que les autres travaillent, moi je dessine” (I prefer to do something else, while the others work, I draw) (p. 13). Examples like these certainly illustrate acts of defiance, but it’s a very different type of defiance than the anti-ought-to self, as mentioned above. These are more akin to classic traits of de-motivation (Falout et al., 2009); however, if one of these students were to exhibit a strong anti-ought-to self, this would be the student who would engage in the language learning task, despite classmates putting pressure not to do so. In other words, the student would excel in language learning, despite pressure from those to do otherwise.

In the Algerian context, Gacemi (2021, this volume) discusses a very different kind of resistance to using the French language: a negative attitude towards the French language among colleagues who are not French instructors. French instructors feel that they should not speak French in the teachers’ lounge because others will feel that they are showing off, as Abdelkrim40 indicates: “il veut se vanter ou quoi?” (He wants to show off or what?) (p. 9). Certainly there is evidence to suggest that others do not accept French in public spaces at school, as Kébir65 states: “c’est mal vu! c’est mal vu! c’est mal vu!” (it’s frowned upon!) (p. 9). Gacemi lays out a framework of resistance due to the fallout of French colonialism and the subsequent struggle for Algerian independence. A student who exhibited a strong anti-ought-to self would want to excel in French, despite the negative attitudes of some of the teachers at school and the resistance to French in the Algerian society. This type of motivation is akin to the L1 Chinese students in Thompson and Liu (2018) who were learning Japanese.

Popica and Gagné (2021, this volume) examine questionnaire data from 974 L1 English-speaking French as a Second Language (FSL) students in Quebec, along with 22 directed interviews and four focus groups from 48 students. The goal was to better understand the attitudes towards and motivations for learning French for these L1 English speakers and to investigate the perceived resistance to learning French. The results indicate that many of the students found their French classes boring, as Mark states: “Very boring (…) We did the same things every year (…) the same grammar, the same verbs” (p. 14, bold in the original), and that they did not feel that they were learning much, as Daniel states: “I found that I didn’t learn much (…) I found that basically, I wasn’t getting what I was supposed to get” (p. 14). In terms of attitudes towards the French-speaking community and the language itself, many of the students found French-speaking Quebecers stuck up, as Andrew states: “Well there’s like a stereotype of French people that classifies them as arrogant and cocky and all that but honestly 95 % of the time it’s true” (p. 17, bold in the original) and Quebec French as being inferior to French from France, as Kevin states: “Québécois is like more slang” (p. 18, bold in the original).

Nonetheless, there was an acknowledgement that when living in Québec, learning French is necessary to get jobs as Daniel states: “It gives you better job prospects” (p. 20, bold in the original) and that French is needed to interact with the majority of the population. Nonetheless, there is real resistance on the part of L1 English speakers in Québec, despite French being the majority language. The resistance comes from the political tensions between French and English-speaking factions in Canada, among other factors (see Figure 6, p. 22). French speakers in Québec feel pride in their language and in a sea of English speakers in the majority of Canada, oftentimes insist on French being spoken. The L1 English speakers in this study resist this notion, and some feel that “French is being shoved down our throats” (p. 24, bold in the original). There is a ray of hope, however; those English speakers who engaged in a higher number of interactions with French speakers had more positive attitudes towards learning French and French speakers themselves. Perhaps it is these learners who will develop a strong anti-ought-to self to become competent French speakers, despite the resistance around them.

There is no doubt resistance to language learning in a variety of contexts. The question is perhaps how to harness this resistance and generate something positive, to resist the resistance, so to speak.

Connecting the anti-ought-to self with other constructs

In the field of applied linguistics, there are other constructs with similar underpinnings to the anti-ought-to self. The most explicitly connected construct is Lanvers’ (2016, 2017) idea of “rebellious motivation” based on data from L1-English speakers from the UK. Citing the anti-ought-to self of Thompson and Vásquez (2015), Lanvers hypothesizes that “motivation for Anglophones learning other languages is perceived to be vulnerable” (2016, p. 83), given the popularity of English world-wide. She also indicates that “Some students of this learner type also displayed the ‘rebellious’ motivational streak wanting to counter the negative language learner image of the British” (p. 87). Lanvers and Chambers (2019) also discuss this concept in light of the increasing dominance of English as a global language, which is at least partially responsible for the decline in popularity in studying LOTEs.

There are other constructs that are just emerging in applied linguistics research that potentially have similar underlying notions than that of the anti-ought-to self: grit, buoyancy, resilience, and flow. Grit has thus far been the one that has been the most researched in relation to language learning.

According to Duckworth and Quinn (2009), grit is “perseverance and passion for long-term goals” (p. 1087). These authors developed and validated a 5-point Likert grit scale, which consists of two underlying latent variables: consistency of interest (i.e. “I often set a goal but later choose to pursue a different one”) and perseverance of effort (i.e. “Setbacks do not discourage me”). See Table 2 below for all of the items in Duckworth and Quinn’s full grit scale (p. 167 from Duckworth and Quinn, 2009).

Table 2: Full Grit Scale from Duckworth and Quinn (2009)

|

Consistency of Interest |

|

1. I often set a goal but later choose to pursue a different one. |

|

2. I have been obsessed with a certain idea or project for a short time but later lost interest. |

|

3. I have difficulty maintaining my focus on projects that take more than a few months to complete. |

|

4. New ideas and projects sometimes distract me from previous ones. |

|

5. My interests change from year to year. |

|

6. I become interested in new pursuits every few months. |

|

|

|

Perseverance of Effort |

|

7. I finish whatever I begin. |

|

8. Setbacks don’t discourage me. |

|

9. I am diligent. |

|

10. I am a hard worker. |

|

11. I have achieved a goal that took years of work. |

|

12. I have overcome setbacks to conquer an important challenge. |

As indicated by the items above, unless reverse coded, the items in the “consistency of effort” category are more accurately asking learners to evaluate their inconsistency of effort. The shortened grit scale (Grit-S) only uses the first four items in each category (i.e. items 1-4 for consistency of interest and items 7-10 for perseverance of effort).

The items in the grit scale that are most connected to the anti-ought-to self construct are those in the perseverance of effort category. Consider the items that are consistently used on the short grit scale in this category: “I finish whatever I begin”; “Setbacks don’t discourage me”; “I am diligent”; and “I am a hard worker.” These are similar in nature to items regularly used in questionnaires to measure the anti-ought-to self, such as “I am studying this language because it is a challenge” and “I want to speak this language because it is not something that most people can do” (see Table 1 above for all items). Teimouri et al. (2020) started with Duckworth and Quinn’s grit scale and created a language-specific grit scale to use with language learners. Via a principle component analysis, the authors found the same two latent variables as with the original grit scale. The items are almost identical as well; for example, in the consistency of interest category, the item “I have been obsessed with a certain idea or project for a short time but later lost interest” became “I have been obsessed with learning English in the past but later lost interest. In the perseverance of effort category, the item “I am diligent” became “I am a diligent English language learner,” and so on. Certainly, the items could be altered to reflect any target language. Similarly, Ebadi et al. (2018) examined a language-specific grit instrument in the Iranian context.

In terms of general academic achievement, grit has been shown to predict school achievement more than other variables such as personality, motivation, and engagement (Steinmayr et al., 2018), and (Usher et al., 2019) looked at grit and self-efficacy for academic success. With language learning, specifically, several studies have shown that grit and L2 achievement are positively related. For example, Wei et al., (2019) examined grit and language performance in light of the mediating variable of foreign language enjoyment and classroom environment with 832 middle school students in the Xinjiang and Anhui provinces in China. There was found to be a positive relationship between grit and language performance; there was also a relationship between grit and enjoyment of the language. Sudina and Plonsky (2020) examine L2 and L3 achievement data from 153 Russian undergraduates in terms of grit and anxiety and found grit to be a relevant construct to examine in terms of language learning achievement. Also looking at grit, while taking language mindset into consideration, Khajavy et al. (2021) found a weak positive prediction between growth mindset and the perseverance of effort category of grit; there was no relationship found between the consistency of effort grit category and mindset.

Buoyancy is another recently-studied variable in the applied linguistics research that employs a similar concept as the anti-ought-to self. Yun et al. (2018) examine the concept of buoyancy in the language-learning classroom: “Buoyancy functions as an adaptive response to frequent, ordinary, and temporary setbacks and challenges in educational settings” (p. 807). The authors postulate that buoyancy is distinct from resilience (reaction to extreme adversity), hardiness (resistance to psychological stressors), and grit (sustained focus on specific goals): “Buoyancy, for its part, is proposed to address how students negotiate the inevitable ups and downs of everyday academic life and how they cope with frequent stressful learning situations and experiences” (p. 807). The authors collected data from 787 Korean university learners of English from six different universities in Seoul. A questionnaire using a 6-point Likert scale was distributed with items focused on buoyancy, self-efficacy, strategic self-regulation, ideal L2 self, anxiety, and teacher-student relationship. Using these variables, the authors modeled five buoyancy profiles among the students: the thriver, the engaged learner, the stiver, the dependent learner, and the disengaged learner (see pp. 816-817 for descriptions of each). Overall, the results “offer support to the role of academic buoyancy in sustaining motivation for language learning…Consistent with prior evidence and our hypotheses, our subsequent analyses showed that the more buoyant L2 learners are, the better their L2 achievement” (p. 824).

The following table illustrates the items used to measure buoyancy in this study; the items are provided in the supplemental materials on the journal’s website. As noted by the authors in these materials, “Items with an asterisk were excluded because they did not load on their respective constructs as hypothesized or did not show discriminant validity.” As such, only the first four items were used in the analysis of the study.

Table 3: Buoyancy items from Yun et al. (2018)

|

Buoyancy |

|

1. Once I decide to do something for English learning, I am like a bulldog: I don’t give up until I reach the goal. |

|

2. In English class, I continue a difficult task even when the others have already given up on it. |

|

3. When I run into a difficult problem in English language class, I keep working at it until I think I’ve solved it. |

|

4. I remain motivated even in activities of English learning that spread on several months. |

|

5. * I believe I have ability to succeed even in English class. |

|

6. * Even if the work is hard, I’m confident I can learn it. |

A less-researched concept in the applied linguistics literature is resilience, potentially because of the supposed extreme nature of the reaction to adversity needed, as described in Yun et al. (2018). Nonetheless, there has been some data collected on this construct, namely Kim et al. (2018), who analyzed data from 367 elementary school students in Gyonggi Province, a region near Seoul. The questionnaire using a 5-point Likert scale developed and used for the study contained 28 items on resilience, along with 33 items on motivation to learn English and 24 items on demotivation to learn English. Of these variables, it was found that demotivation had the strongest effect on English proficiency. At the time of writing this article, the full questionnaire was not publicly available. However, sample items were given for the three constructs; the items used to measure resilience are below.

Table 4: Sample resilience items from Kim et al. (2018)

|

Resilience |

|

1. I can identify the problem in most situations. |

|

2. I have few friends from whom I can seek help. (reverse coding) |

|

3. I am satisfied with my life. |

|

4. If a task does not progress as I expect, I usually give up. (reverse coding) |

|

5. I know how other people feel when I observe their facial expressions. |

From the information on the items provided, it seems that some of them are related to the anti-ought-to self, such as item 4 above: “If a task does not progress as I expect, I usually give up. (reverse coding).” However, access to the full questionnaire is needed to analyze this relationship further. It is also the case that 28 items for one construct would be too many to use if someone were to want to measure a variety of different constructs in one questionnaire; thus, potential items would need to be eliminated via variable reduction techniques such as an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). There have also been a limited number of studies on language teaching (as opposed to learning) and resilience. Hiver (2018) provides a detailed overview of the construct and the relevance to language teaching. In their qualitative study, Kostoulas and Lämmerer (2018) examine interview data of Claire, a teacher educator, to illustrate her transition into a new position.

The concept of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 2008), which is the “intrinsic motivational state characterized by positive affect and full cognitive engagement that occurs when learners are immersed in meaningful and challenging, but doable activities, with clear goals, a sense of agency and internal feedback” (Zuniga & Payant, 2021, p. 49), could also potentially be linked to the concept of the anti-ought-to self. In a study with 24 university-level learners of English as an Academic language, Zuniga and Payant (2021) examined the relationship between task and procedural repetition across modalities and flow. For the questionnaire aspect of the study, there were three parts: 14 items for background information, 14 items for flow perceptions, and 5 open-ended items about task appreciation. The full questionnaire was not available for analysis; however, the authors explained that the flow questionnaire had items related to interest, attention focus, and control, along with items to measure the skill-challenge balance. The results indicated learners’ flow experience to be positively influenced by repetition, with modality also interacting in a meaningful way. Being able to see all of the items in the questionnaire would be helpful in determining the relationship between flow and the anti-ought-to self.

Table 5: Sample flow items from Zuniga and Payant (2021)

|

Flow |

|

1. This task excited my curiosity. (interest) |

|

2. When doing this task, I was aware of distractions. (attention focus) |

|

3. I felt that I had not control over what was happening during this task. (control) |

|

4. This task was too hard. (skill-challenge balance) |

|

5. This task was too easy. (skill-challenge balance) |

Future directions

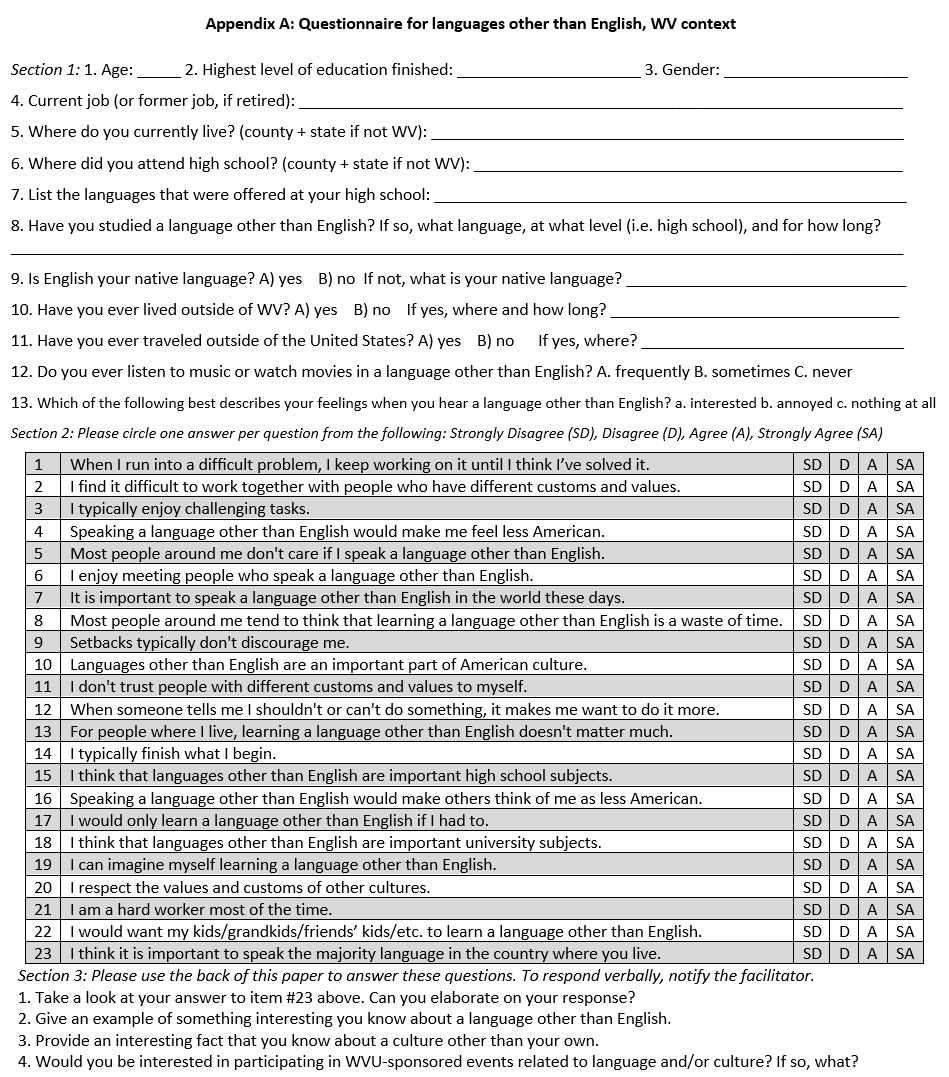

Constructs such as the anti-ought-to self and related constructs, such as grit and buoyancy, have typically been examined in the context of larger urban areas. Certainly, this is to be expected, and the population density and relative proximity of multiple data collection sites in the form of schools or universities makes data collection in more populated areas the logical choice. Nonetheless, examining those in rural contexts could provide different insights. The learning experience, which is the aspect of the L2MSS that focuses on contextual variables rather than self concepts, would vary based on aspects such as different language learning environments. I have recently embarked on a community-focused project in my current location, West Virginia, about attitudes toward and accessibility to learning a language other than English, which is supported by the West Virginia Humanities Council. In a predominantly rural state that has relatively little linguistic (97.5 percent L1 English speakers) and racial (92.1 percent white) diversity (see Hazen, 2018 and Thompson, 2022, for details about state demographics), I endeavored to investigate the attitudes that people have toward LOTEs, as well as the accessibility to language learning that these individuals had while attending high school in the state. I also felt that it was important to collect data from individuals other than students, which poses difficulties in data collection; as faculty members, we have the most readily available access to students to collect our data. Nonetheless, I proposed to collect data in locations where students might be, but where they would not be the majority: festivals, farmer’s markets, and retail outlets, such as Tractor Supply.

The data collection instrument has 13 background questions, 23 4-point Likert scale items, and four optional open-ended questions that can be answered verbally or in writing. In fact, when collecting the data, I gave the participants the choice for the questionnaire to be read out loud with me marking the answers so that I could gather information from people with a variety of educational backgrounds. The questionnaire was created and piloted over a period of a few weeks with community members who are not affiliated with the university. I wanted the questionnaire to fit onto one single-sided page when printed out and to be able to be answered in under five minutes, with the exception of the open-ended questions. The paper-based questionnaires are on multiple clipboards arranged on a folding table in the face-to-face data collection locations. Participants can also choose to scan a QR code and answer on their phones, if this is their preference; there is also an online version of the questionnaire that is being distributed via listservs and social media outlets.

The Likert-scale items consisted of the constructs of buoyancy (item 1), ethnocentrism (items 2, 11, and 20), anti-ought-to self (items 3 and 11), fear of assimilation (items 4, 10, and 16), milieu (items 5, 8, 12, 15, and 18), attitudes towards the L2 community (item 6), instrumentality (item 7), grit, (items 9, 14, and 21), ought-to self (item 17), ideal self (item 19), and two additional items suggested during the pilot testing period (items 22 and 23). Certainly, more items per construct would have been preferable, but choices had to be made to keep the questionnaire the desired length. Appendix A contains a full, printable version of the questionnaire.

Although the data collection was still underway at the time of writing this article, the preliminary results are not necessarily what one might think. In some cases, people do not necessarily understand why LOTEs should be learned; however, there is oftentimes not the strong resistance that might be expected in such a context. The trends also indicate that, although there is not a preponderance of linguistic diversity in the state, people tend to want their kids, grandkids, or friends’ kids to have the opportunity to learn a language other than English. More complete results will be disseminated in the coming months; however, the preliminary results are encouraging: there does not seem to be as much resistance to learning LOTEs in the rural context of West Virginia as one might have predicted.

The results of this project fill the gap in a variety of ways. The participant pool provides needed information from people outside of typical applied linguistics research (i.e. members of the community, rather than students and/or faculty). The context of the study will help us gain insights into attitudes towards LOTEs in a rural setting, which is something that is not often done. Finally, items from a variety of constructs that measure resistance to pressure and thriving in challenging situations (i.e. anti-ought-to self, grit, and buoyancy) were included so that they can be examined in tandem. Indeed, the potential of and interest in acts of resistance in language learning, such as the anti-ought-to self, are growing, as indicated by this special issue of Travaux de didactique du français langue étrangère (TDFLE). Certainly, this is an important facet to understanding language learning motivation, and exploring it in additional contexts with participants from a variety of backgrounds will serve to increase our knowledge base in this area.

Acknowledgement: This project is being published with financial assistance from the West Virginia Humanities Council, a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations do not necessarily represent those of the West Virginia Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

![]()

References

Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2018). The L2 motivational self system: A meta-analysis. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 8(4), 721–754. https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/ssllt/article/view/12295

Amorati, R. (2021). The motivations and identity aspirations of university students of German: A case study in Australia. Language Learning in Higher Education, 11(1), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1515/cercles-2021-2007

Brehm, J. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Academic Press.

Busse, V., & Williams, M. (2010). Why German? Motivation of students studying German at English universities. The Language Learning Journal, 38(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571730903545244

Chen, Y., Zhao, D., & Qi, S. (2021). Chinese students’ motivation for learning German and French in an intensive non-degree programme. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a La Comunicación, 86, 81–93. https://doi.org/10.5209/clac.75497

Crossley, S. A. (2018). Technological disruption in foreign language teaching: The rise of simultaneous machine translation. Language Teaching, 51(4), 541–552. http://dx.doi.org.wvu.idm.oclc.org/10.1017/S0261444818000253

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (2nd ed.). Harper & Row.

Csizér, K., & Lukács, G. (2010). The comparative analysis of motivation, attitudes and selves: The case of English and German in Hungary. System, 38(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2009.12.001

Deping, L. (2003). Japan in the eyes of Beijing’s university students. Chinese Education & Society, 36(6), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932360655

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9–42). Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z., & Al‐Hoorie, A. H. (2017). The Motivational foundation of learning languages other than Global English: Theoretical issues and research directions. The Modern Language Journal, 101(3), 455–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12408

Dörnyei, Z., & Taguchi, T. (2010). Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration and processing (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the short grit scale (Grit–S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

Ebadi, S., Weisi, H., & Khaksar, Z. (2018). Developing an Iranian ELT context-specific grit instrument. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 47(4), 975–997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10936-018-9571-x

El Houda El Abbadi, N. (2021). Les facteurs et les formes de résistances des apprenants marocains face à l’acte d’écrire. Revue TDFLE, 78, 1–25. https://revue-tdfle.fr/articles/revue-78/2561-les-facteurs-et-les-formes-de-resistances-des-apprenants-mar ocains-face-a-l-acte-d-ecrire

Falout, J., Elwood, J., & Hood, M. (2009). Demotivation: Affective states and learning outcomes. System, 37(3), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2009.03.004

Gacemi, M. (2021). Attitudes et discours négatifs comme cause de la résistance à l’apprentissage du français en Algérie. Revue TDFLE, 78, 1–13. https://revue-tdfle.fr/articles/revue-78/2559-attitudes-et-discours-negatifs-comme-cause-de-la-resistancea- l-apprentissage-du-francais-en-algerie

Goldberg, E., & Noels, K. A. (2006). Motivation, ethnic identity, and post-secondary education language choices of graduates of intensive French language programs. The Canadian Modern Language Review / La Revue Canadienne Des Langues Vivantes, 62(3), 423–447. https://doi.org/10.1353/cml.2006.0018

Hazen, K. (2018). Rural voices in Appalachia: The shifting sociolinguistic reality of rural life. In E. Seale & C. Mallinson (Eds.), Rural Voices: Language, Identity, and Social Change across Place (pp. 75–90). Rowman & Littlefield.

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-Discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

Hiver, P. (2018). Teachstrong: The power of teacher resilience for second language practitioners. In S. Mercer & A. Kostoulas (Eds.), Language teacher psychology (pp. 231–246). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783099467-018

Huensch, A., & Thompson, A. S. (2017). Contextualizing attitudes toward pronunciation: Foreign language learners in the United States. Foreign Language Annals, 50(2), 410–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12259

Khajavy, G. H., MacIntyre, P. D., & Hariri, J. (2021). A closer look at grit and language mindset as predictors of foreign language achievement. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 43(2), 379–402. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0272263120000480

Kim, T.-Y., Kim, Y., & Kim, J.-Y. (2018). Role of Resilience in (De)Motivation and Second Language Proficiency: Cases of Korean Elementary School Students. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 48(2), 371–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-018-9609-0

Kostoulas, A., & Lämmerer, A. (2018). Making the transition into teacher education: Resilience as a process of growth. In S. Mercer & A. Kostoulas (Eds.), Language teacher psychology (pp. 247–263). Multilingual Matters.

Lamb, M. (2012). A self system perspective on young adolescents’ motivation to learn English in urban and rural settings. Language Learning, 62(4), 997–1023. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2012.00719.x

Lanvers, U. (2016). Lots of selves, some rebellious: Developing the self discrepancy model for language learners. System, 60, 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.05.012

Lanvers, U. (2017). Contradictory others and the habitus of languages: Surveying the L2 motivation landscape in the United Kingdom. The Modern Language Journal, 101(3), 517–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12410

Lanvers, U., & Chambers, G. (2019). In the shadow of Global English? Comparing language learner motivation in Germany and the United Kingdom. In M. Lamb, K. Csizér, A. Henry, & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 429–448). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28380-3_21

Lanvers, U., Thompson, A. S., & East, M. (Eds.). (2021). Language Learning in Anglophone Countries: Challenges, Practices, Ways Forward. Palgrave MacMillan.

Laurin, K., Kay, A. C., Proudfoot, D., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2013). Response to restrictive policies: Reconciling system justification and psychological reactance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 122(2), 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2013.06.004

Liu, M., & Zhao, S. (2011). Current language attitudes of mainland Chinese university students. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 2(5), 963–968. https://doi.org/doi:10.4304/jltr.2.5.963-968

Liu, Y., & Thompson, A. S. (2018). Language learning motivation in China: An exploration of the L2MSS and psychological reactance. System, 72, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.09.025

MacIntyre, P. D. (2002). Motivation, anxiety and emotion in second language acquisition. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Individual differences and instructed language learning (pp. 45–69). John Benjamins. https://benjamins.com/catalog/lllt.2.05mac

Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41, 954–969. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954

Mendoza, A., & Phung, H. (2019). Motivation to learn languages other than English: A critical research synthesis. Foreign Language Annals, 52(1), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12380

Oakes, L. (2013). Foreign language learning in a ‘monoglot culture’: Motivational variables amongst students of French and Spanish at an English university. System, 41(1), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.01.019

Pastushenkov, D., & McIntyre, T. (2020). Life after language immersion: Two very different stories. Journal of the National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages, 27, 1–32.

Popica, M., & Gagné, Ph. (2021). Je résiste, donc nous sommes. Revue TDFLE, 78, 1–38. https://revue-tdfle.fr/articles/revue-78/2560-je-resiste-donc-nous-sommes

Salaberri-Ramiro, M. S., & Sánchez-Pérez, M. del M. (2018). Motivations of higher education students to enrol in bilingual courses. Monográfico III, 61–74.

Steinmayr, R., Weidinger, A. F., & Wigfield, A. (2018). Does students’ grit predict their school achievement above and beyond their personality, motivation, and engagement? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 53, 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.02.004

Sudina, E., & Plonsky, L. (2020). Language learning grit, achievement, and anxiety among L2 and L3 learners in Russia. https://doi.org/10.1075/itl.20001.sud

Teimouri, Y., Plonsky, L., & Tabandeh, F. (2020). L2 grit: Passion and perseverance for second-language learning. Language Teaching Research, online first. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1362168820921895

Thompson, A. S. (2022). Language learning in rural America: Creating a ideal self with limited resources. In A. H. Al-Hoorie & S. Fruzsina (Eds.), Researching laguage learning motivation: A consise guide (pp. 99–110). Bloomsbury.

Thompson, A. S. (2017a). Don’t tell me what to do! The anti-ought-to self and language learning motivation. System, 67, 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.04.004

Thompson, A. S. (2017b). Language learning motivation in the United States: An examination of language choice and multilingualism. The Modern Language Journal, 101(3), 483–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12409

Thompson, A. S., & Erdil-Moody, Z. (2016). Operationalizing multilingualism: Language learning motivation in Turkey. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 19(3), 314–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2014.985631

Thompson, A. S., & Liu, Y. (2018). Multilingualism and emergent selves: Context, languages, and the anti-ought-to self. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1452892

Thompson, A. S., & Vásquez, C. (2015). Exploring motivational profiles through language learning narratives. The Modern Language Journal, 99(1), 158–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12187

Usher, E. L., Li, C. R., Butz, A. R., & Rojas, J. P. (2019). Perseverant grit and self-efficacy: Are both essential for children’s academic success? Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(5), 877–902.

Wei, H., Gao, K., & Wang, W. (2019). Understanding the relationship between grit and foreign language performance among middle school students: The roles of foreign language enjoyment and classroom environment. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01508

Xie, Y. (2000). French as a Foreign Language Instruction. Europe Plurilingue, 9, 87–93.

Yun, S., Hiver, P., & Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2018). Academic Buoyancy: Exploring learners' everyday resilience in the language classroom. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 40(4), 805–830. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263118000037

Zuniga, M., & Payant, C. (2021). In flow with task repetition during collaborative oral and writing tasks. The Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 24(2), 48–69.